Each decade has its own set of well-loved, overused, business buzzwords. The 80’s gave us ‘low-hanging fruit’ and ‘bottom-line’, the 90’s ‘streamline’ and ‘leverage’, whilst the 2000’s gave us ‘synergy’.

One of this decade’s top buzzwords is ‘sustainability’. But unlike most buzzwords, the word ‘sustainability’ is overused with good reason. That being that we live in a world with diminishing natural resources, and a growing population.

As a result, the UN is reporting that, “2016 is slated to be hottest year ever, with record-breaking emissions and melting Arctic ice.” While the WWF states that, “A new economic path towards sustainability is both a necessity and a huge opportunity.”

It is this necessity and opportunity that is directing the chemical industry’s thinking.

Take for example, the fact that the chemical company Henkel, includes sustainability as one of four main criteria for supplier selection (the others being price, on-time delivery and product quality). Given that Henkel is a very successful company, with 50,000 employees, and an €18 billion turnover, which operates brands such as Persil, Fa, Schwarzkopf, Pritt, Locktite and Dial, then other chemical companies would do well to follow their lead.

In fact, given the number of suppliers Henkel cooperates with, chemical traders or manufacturers need to source their feedstock wisely if they wish to do any business at all.

This is a point that Christine Schneider, Head of Global Sustainability in R&D in Laundry and Home Care at Henkel, made clear in her presentation at CIEX Europe 2016, a unique platform created for R&D and innovation experts from the consumer, industrial and specialty chemical sectors.

You can watch her full video presentation below (30 mins):

Here she opened up about some of the challenges chemical companies face in improving sustainability, and talked about the processes Henkel had in place to achieve their targets.

Sustainability Targets

Indeed, one of the first steps to success in sustainability is establishing targets, with Henkel setting out in 2010 with a simple goal to triple sustainability over the next 20 years. They aim to achieve this by increasing sales by 50% in that time, while halving the footprint of raw chemical material sourcing.

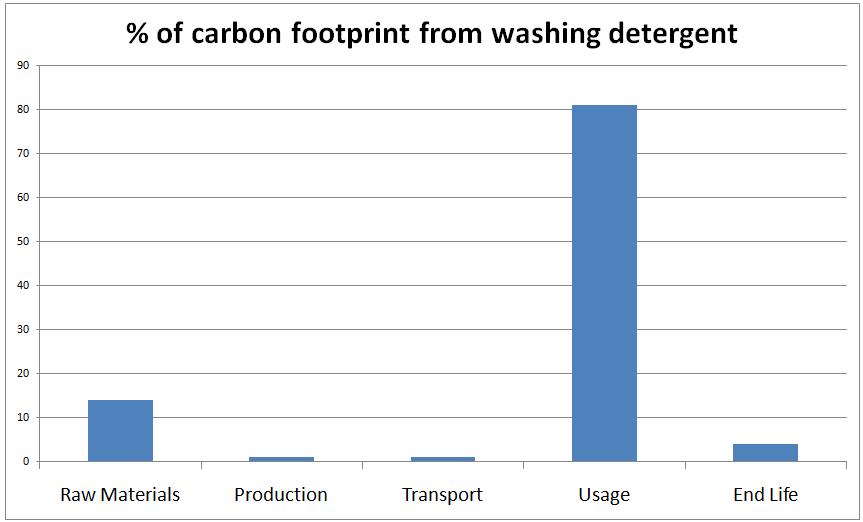

The second step a chemical company needs to take is analysis; the need to study a product’s environmental impact. This should take into account all the stages of its life, including the resources used during the product’s (even domestic) consumption. Schneider gave the example of washing detergent, and explained how much of this product’s impact was in packaging or in heating the washing water. As a result, a ‘life cycle assessment’ of detergent showed the phase that causes the biggest carbon footprint was ‘usage’, which creates 81% of a detergent’s ‘ungreenliness’.

As is evident in the graph, much of the challenge in making many domestic products more sustainable is that the largest carbon footprint process is out of the manufacturer’s control. If Henkel could persuade its customers to wash their laundry at 30°, instead of 40°, then the brand Persil would reduce CO² emissions by 500,000 tons a year.

As is evident in the graph, much of the challenge in making many domestic products more sustainable is that the largest carbon footprint process is out of the manufacturer’s control. If Henkel could persuade its customers to wash their laundry at 30°, instead of 40°, then the brand Persil would reduce CO² emissions by 500,000 tons a year.

But by analysing the data, any efforts to make Persil a more sustainable product can now focus on the heart of the problem. Without analysis, any sustainability drive may focus on the wrong goal, and any success would be immeasurable.

The third step towards sustainable chemical products was traceability. This was achieved by tracking where a raw material originated from, how it was sourced, how it was transported and refined, and knowing who was involved in each process. This traceability includes following the route that waste products take, as well as what happens to chemical products after they have been used and are at the end of their lives.

To do this, Henkel recommends working closely with suppliers, building long-term understandings, and sharing information about sourcing and sustainability issues. Co-operating with NGO’s, such as WWF and Greenpeace, also allows companies access to advice and helps with the sharing of ideas and efforts towards a mutual goal. This not only allows for ‘sustainability credentials’ to be openly verified, but also saves money, as the company can adopt a ‘one audit’ process, that is used by both chemical supplier and manufacturer to confirm the sustainability of feedstock.

Schneider also stated that, “Another very good initiative is [that we] reward our suppliers; one example being Novozyme, who won Henkel’s ‘Best Sustainability Award in Laundry and Home Care’. [They won] for their work in producing a better enzyme mix, with more high performing enzymes which could reduce the surfactant content, which is a driver when it comes to counting carbon footprint.”

The issuing of awards was also part of a concerted effort to establish a public commitment towards sustainability. This acts not only to promote the company’s efforts in a positive light, but also makes the public aware of the issues at hand. This could lower wastage, help recycle packaging, lower wash temperatures etc, as well as help guide the company towards its goals, as sustainability becomes a public and declared intent.

This is why Henkel has joined the initiative of ‘Zero net deforestation by 2020’, in an attempt to reduce the impact of the company’s sourcing of palm oil.

To the future, Henkel is looking to innovation to improve its sustainability. The use of fossil fuel alternatives, such as coconut oil, lignite or algae oils are being studied, but may be as far as 20 years from becoming a core chemical feedstock.

Despite all these efforts, the fact remains that sustainability is a hard nut to crack. It will require a lot of time, effort and money from everyone involved with chemicals if the industry is to become what it needs to become. But given the health of the planet, given the public’s desire for sustainable products, given the moral obligation chemical traders and manufacturers have to source responsibly. Isn’t doing good a necessary evil?

This blog is written by Simon Hilton and originally posted on Spotchemi blog.

Photo credit; SINCHEM Luca Cervone, Monica Palmirani

[adrotate group=”1″]